A slightly different version of this article was first published at Your Wardrobe Unlock’d. You may wish to read Part I before continuing.

(Click any illustration to view the full-sized image.)

The Victorians had very strict rules for dressing. In the first half of this article, we looked at the many types of women’s daytime clothing and determined when each outfit was appropriate. Now, let’s examine two more aspects of historic costume: gowns for evening wear and sportswear.

Evening

In the evening, all the rules change: necklines can be daringly low; sleeves can be short, or non-existent; glittering jewelry can be worn. There are several classes of evening gowns, including dresses worn specifically for dinner, for the opera, or for a ball. Gloves should be longer than in the daytime, but hats or bonnets are no longer necessary. Instead, a woman can wear flowers, feathers, or jewels in her hair.

The following are types of evening dresses:

|

|

|

Dinner Dress

In America, the dinner dress is less decorative than in England or Europe. Unless you plan to attend another event after dinner, keep your dress relatively unadorned. After all, much of the gown will be concealed by the dining table. A dinner gown must have sleeves, even if short, and the neckline should not be low; too much bare skin is inappropriate for the dinner table. Formal fabrics trimmed with lace are popular for evening. Colors should be somber: black, dark, or neutral shades.

“Gloves . . . are now removed at the table,” but lace mittens may be kept on.—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 76 (1870)

Satin boots are perfectly acceptable. A headdress of ribbon or velvet may be worn. Note, however, that: “Flowers, unless they be natural ones in summer, are in very bad taste, excepting in cases where a party of invited guests are expected.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pg 28 (1872)

Sociable Dress

Casual affairs, such as impromptu gatherings, party rehearsals, and dramatic readings, all fall under the heading of the sociable. This is not an affair for full-dress, but some pains should be taken with your appearance. Wear “. . . a dress of rich material made to cover the arms and shoulders, yet trimmed to have a dressy appearance.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 80 (1870)

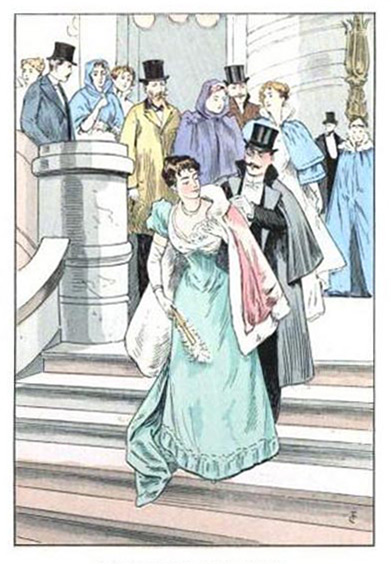

Opera Toilette

Rules for the opera vary according to city, but ladies in attendance are meant to be seen. At large, metropolitan operas, full evening dress should be worn. This means a low, wide neckline that bares the shoulders, and of course, the finest of fabrics. Silks are preferable. Light materials, such as tulle, should be avoided, as they will be crushed in the crowds.

An opera cloak is a must; however, any cloak or lace shawl should be removed while indoors, so as to better display your gown. White is most fashionable for an opera cloak, but other colors may be worn, provided they don’t clash with your dress. The cloak must be richly embroidered or trimmed. Opera bonnets are optional, and are only worn at operas where full dress is not mandatory. “If a bonnet [is worn], the arms and neck should be covered.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 86 (1870)

White kid gloves must be worn, or else very pale tints. Rich jewelry is expected. Hair may be dressed with artificial flowers, ribbons, lace, jewels, feathers, or other ornaments. Accessories should include a fan, a small bouquet of flowers, a handkerchief, and a lorgnette.

Theater Dress

Women are meant to be seen while attending the opera, but the opposite is true for attending the theater. Your dress should be modest and subdued. “The dress for the theater, excepting some especial occasion, when full-dress is worn, is generally that worn for the promenade.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 90 (1870)

Street bonnets should be worn, or even a hat, along with a loose shawl or cloak that can be removed if it becomes too warm. Gloves should be of kid and colored—not white—to coordinate with your dress.

Ballgown

Worn for the ultimate evening affair, a ballgown is suitable also for the soirée. It is considered full dress, which means the throat and shoulders are bared completely. Ballgowns may be trained or not, as you desire.

Fabrics depend upon your age. For older ladies, materials must be rich and luxurious, such as heavy satin, velvet, and silk moire.

For younger ladies, however, lighter fabrics are more appropriate: “Tulle, plain and embroidered, worn over silk, tarletan, muslin, grenadine, barege, silk tissue, crape, lace, illusion, and other thin fabrics . . . are all becoming for evening-dresses.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 82 (1870)

Anything somber is out of place in a ballroom, so keep colors cheerful and light. Jewelry is acceptable: necklaces, bracelets, and hair ornaments. Gloves must be worn, preferably white. White shoes or boots are most appropriate, unless the gown is black, but boots may also be dyed to match the gown, and slippers may be trimmed to match.

Sportswear

A new class of garment, sportswear accommodates the needs of women who are becoming more and more active as the years go by. In the 1850s, Amelia Bloomer sparked the trend by wearing the now-infamous “Bloomer” costume, comprised of a short dress with trousers beneath. Practical variations of the Bloomer exist for bicycling and skating, as well as bathing.

The following are some types of sportswear:

|

|

|

Skating Costumes

Meant to be worn while roller or ice skating, these dresses are simplified and shortened. For ease of movement, the bodice should be well-fitting and snug. “The skirts must clear the ankle, and the sacque or basque must leave the arms perfectly free.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 57 (1870)

An alternative to the short skirt is to wear a knee-length polonaise with loose trousers beneath.

Winter outfits are often of velvet trimmed with fur, but may also be of cashmere, merino, or poplin trimmed with velvet, ribbon, or braid. For reasons of safety, keep trimmings secure and avoid loose veils or ribbons. Deep, rich, warm colors, such as wine red, brown, navy, dark purple, emerald or forest green, and camel, are preferred. Kid boots should be worn, preferably trimmed with fur, along with fur-trimmed gloves, a small muff, and hat. Also, “Ear caps of fur are comfortable, and becoming.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 59 (1870)

Hunting Ensemble

This outfit is meant to be worn out-of-doors while hunting. Early on, it could be a simple walking dress made with economy. In later years, a hunting dress might be comprised of a mid-calf length skirt and snug trousers. Fashionable colors include earth-tones, such as browns and greens; plaids and tweeds are very popular.

Riding Habit

For centuries, women have worn long skirts while riding sidesaddle. Their only concessions to the hazard of the sport is to leave off whatever support garment happens to be popular at the moment, such as a hoop skirt or bustle, and to wear shorter corsets for comfort while sitting. Typical riding habits include a short, tight bodice, and a trained skirt that is longer on the left side. This excess fabric conceals the legs while riding and usually buttons up out of the way while walking. Habits should “fit the figure perfectly, yet easily,” without wrinkling or being too tight. “The most becoming and appropriate riding dress is made to fit the waist closely, and button to the throat, with sleeves (coat pattern) coming to the wrist.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 53 (1870)

Bright colors are unfashionable for riding habits; dark, neutral colors are preferred. Collar and cuffs should be of linen, while waterproof broadcloth is a good fabric for the habit itself. In summer, heavy linen or nankeen may be worn, so long as the skirt’s hem is weighted to prevent the fabric from flying about. For safety, trimming should be minimal: buttons and braid, but never ruffles. A hat must always be worn, but one that is trim and compact, without loose feathers or ribbons. Boots and gloves should be sturdy enough to withstand the rigors of horseback riding.

Cycling Ensemble

It’s obvious that a woman seriously endangers herself by trying to cycle in long skirts and petticoats. A variation on the Bloomer costume is called for while cycling in the later decades. It consists of a split skirt, or else long, full trousers that tuck into a pair of tall boots, and a short, tightly-fitted bodice. No skirt or petticoat should be worn, because these could easily be caught in the gears of the bicycle. Brown is a popular color for cycling, as it doesn’t show the dirt of the road. Fabrics should be sturdy and not easily wilted or torn.

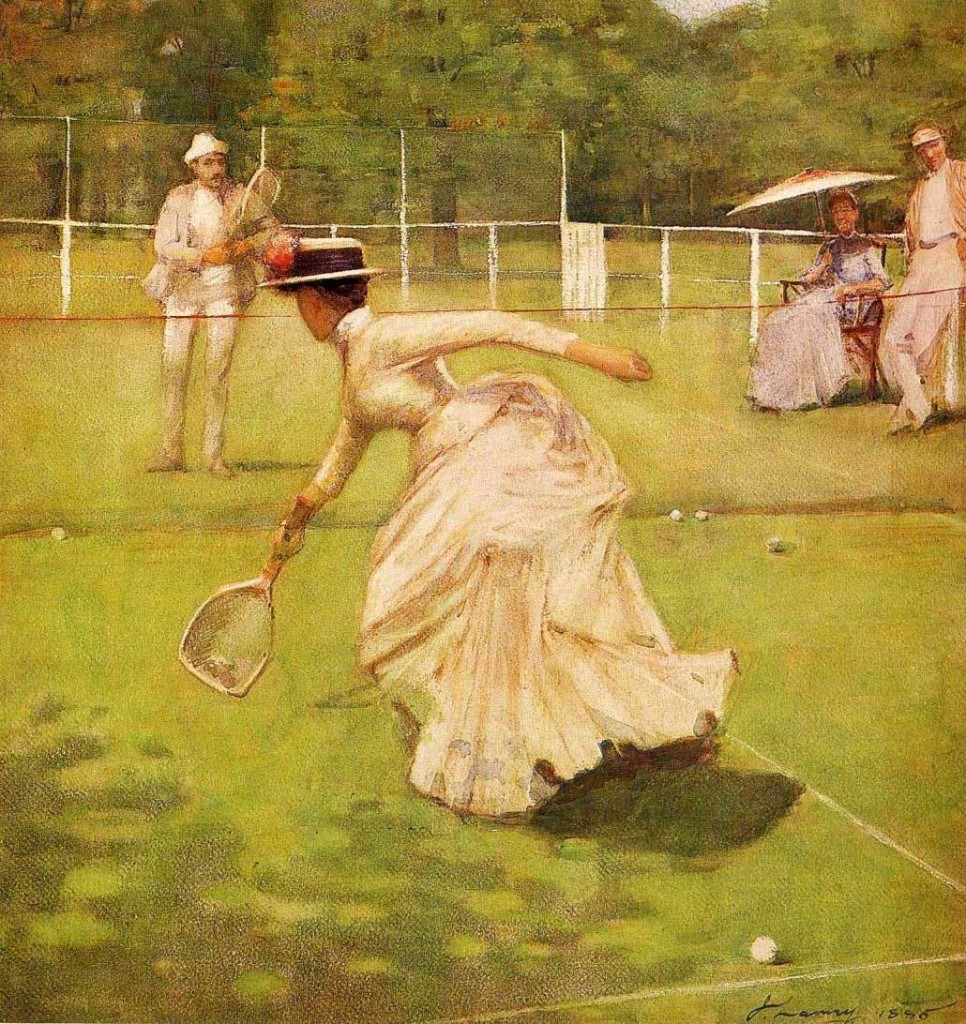

Tennis or Croquet Dress

Meant for gentle outdoor sports, these dresses should be cut so as to allow freedom of movement. “The dress must be made tight-fitting, without sacque or shawl, as a free motion of the arms is essential to skill and grace in the game.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 56 (1870)

Hems should be as short as a walking dress, coming just to the ankle. Keep fabrics lightweight, so you won’t overheat. Colors may be bright and cheerful. Fetching boots should be worn to coordinate, in either leather or cloth. Gloves must be worn, but of lightweight cloth, not heavy kid. For croquet, a wide-brimmed hat will shield you from the sun.

Bathing Suits

Typically made of dark-colored wool flannel, a bathing suit consists of a short dress and trousers, and is meant to be worn while bathing in a lake or ocean. “The best style is a loose waist, belted in, with a skirt falling about halfway between the knee and the ankle, and made quite full.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 91 (1870)

Trousers may be ankle-length or just below the knee, worn with dark stockings or socks for modesty’s sake. In keeping with the nautical theme, popular colors include navy, black, and gray, with trims of red and white. Be certain your trims are colorfast or your bathing suit will be ruined as soon as it gets wet! Slippers that lace around the ankles may be worn, along with an oilskin cap to keep the hair dry.

Bonus! Children’s Wear

In general, children wear miniature copies of adult clothing. Their dresses might be simplified a bit, but once they come out of the unisex gowns that all infants and toddlers wear, girls put on training corsets, along with tiny hoop skirts or bustles. The only allowance made for their age is the length of their skirts. Very young girls wear knee-length dresses, and as they grow, their skirts are let down.

Conclusion

In the course of this article, we examined the rules for Victorian dress, discovered the differences between each type of garment, and learned which accessories are appropriate for each outfit. How is this knowledge practical? The next time you find an unlabeled fashion plate, you might be able to judge its nature. By looking at the neckline and sleeves, you should be able to narrow down the time of day the dress was worn. Looking at the details and accessories, you may even determine exactly what sort of dress is depicted.

Then, too, have you ever been invited to a costuming event and worried over what type of gown to wear? Knowing what kinds of garments were appropriate for daytime and evening will help you choose something suitable for the occasion.

Besides, how can you break the rules if you don’t know them?

References

- The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness by Florence Hartley, 1872

- The Art of Dressing Well by S. Annie Frost, 1870

- Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management by Isabella Beeton, 1861

- Harper’s Bazar Magazine, 1869 & 1873