by Lisha Vidler

(This article first appeared at Your Wardrobe Unlock’d.)

Are you tired of mixing and matching patterns to create a costume that looks just like everyone else’s? Are you bored with trying to recreate fashion plates? If you’ve “been there, done that” and now want to make a truly original Victorian costume, read on!

~~*~~

As a new dressmaker, you might choose a particular pattern and sew it straight up. As you improve, you branch out and begin mixing and matching patterns. You might add embellishments to make something more individual. Once you’ve become advanced, you might decide to recreate a costume from a film or antique fashion plate. But suppose you’ve done that? What if you now desire to make a gown that is not a direct copy of a fashion plate, or using a pattern that plenty of other people have made? . . . Suppose you want to design an original Victorian costume?

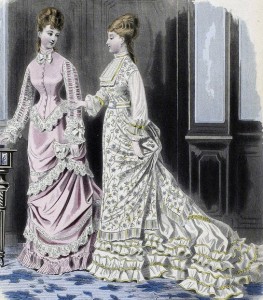

First, regardless of your skill level, you’ll need to decide whether you want this costume to be one hundred percent historically accurate or not. If you’re willing to fudge a bit, you’ll have considerable leeway in your design. However, suppose you want your costume to be entirely historic? Something that no one’s seen before, and yet which would be right at home on the pages of La Mode Illustrée, Godey’s Home Journal, or Harper’s Bazar?

You have two options: the intermediate method is to create a composite design. In this method, you’ll mix and match patterns and design elements, to come up with something unique. The advanced method is to design a complete costume on your own, using historic designs as inspiration. Either way, you’ll need to do considerable research. Browse through photographs of original antique garments and fashion plates. There are plenty of websites and books that can provide inspiration.

Narrowing It Down

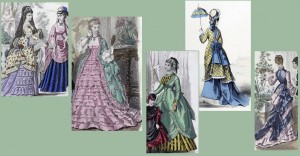

As you browse, make note of which fashions you are continually attracted to. Use your preferences to help you decide which basic period your gown belongs to. Do you adore asymmetrical overskirts, or do you keep coming back to the elegance of a long trained skirt?

Your preference could help you decide between the late 1870s and the mid-1880s. If you like a plain skirt, without a lot of trimming or overskirts, but you dislike hoops, you could aim for a transition gown of 1869-1870.

As for what type of garment it will be, do you prefer off-the-shoulder bodices with tiny puffed sleeves? Are you more into a square neck with three-quarter sleeves, or perhaps a modest neckline and long sleeves? That may help you choose between a ballgown, an evening gown, and a day dress, respectively.

Certain details can be limited based on the type of gown you want, but there are blurred lines. The Victorians had gowns for every occasion, so you’re sure to find something suitable. For example, if you’d like a low neckline, but would prefer longer sleeves, you could make a dinner dress, which typically had a low, square neck and elbow-length sleeves. If you’d like a day dress, but you can’t stand high necklines, call it a visiting gown. If you want to go all out with ruffles and trimmings, but you can’t afford satin and lace, make it a promenade dress.

Once you’ve narrowed down the period and basic style of gown you want, you can begin to select individual details. Look through your collection of fashion plates and photographs, but limit your browsing to the basic period you’ve chosen, with a year or two leeway on either side. This will help ensure that your costume properly reflects the designated era. Remember, too, that styles didn’t simply pop into existence. There were transitional periods for any new element, so you may use certain early bustle details on a natural form gown, or late bustle details on a belle epoch costume.

Sketching It Out

In order to not get overwhelmed, try to focus on one particular at a time and draw it out. Start with a blank figure, such as a paper doll base or croquis. Use tracing paper layered over the croquis to sketch the part of the costume that you’re working on, such as the skirt or bodice. For simplicity’s sake, you might choose to work on the skirt first, then add other layers on top of that.

If you’re going the intermediate route—that is, a composite design—draw your images based on the patterns you’ll be working with. Decide now what changes you’d like to effect in order to make your skirt unique. Perhaps several rows of ruching at the hem, or a deep pleated ruffle?

Draw the basic shape, and then move onto the next layer: an overskirt, then a bodice.

Add embellishments that you’ve seen on fashion plates and original antique garments. Feel free to use elements from different sources, but try to keep the overall design harmonious. It needs to look as though all the pieces go together. The finished costume should be familiar, in that it uses the patterns you already have, but it will certainly have a unique twist to the design.

Once you’ve decided on the details, trace out a copy of the entire costume. Then you can begin experimenting with color. A few books contain fashion plates with their original colors, and there are many colored plates available online for perusal. From these you can see that our ancestors were not afraid to mix and match colors!

You can also find ideas by reading the descriptions found in the books mentioned above. Keep in mind that patterned fabrics are very Victorian, so you needn’t stick to solid colors. Stripes, florals, and plaids were common; even polka dots can be found in period fashion plates!

Advanced Design

Now, if you’re ready for the advanced route—that is, designing a completely original costume—you’ll need to take things a bit further. Begin as you would before, by combing through photographs and fashion plates to get an idea of what you like. Perhaps you fancy the trimming from one gown, but the draping of another, and the silhouette of a third.

As before, you should begin by tracing a basic skirt shape. Using a second piece of tracing paper, draw the overskirt on top of the skirt. Repeat the process for the bodice and sleeves, using different sheets of tracing paper so that you can layer different styles and see how they look together. Don’t forget to do a view showing the back, as well.

When you have a basic combination that you like, trace the entire design onto a fresh piece of paper, and then begin adding embellishments: ruffles, flounces, pleats, ruching, shirring, reveres, epaulettes, piping, vandykes, passementerie, fringe, embroidery, lace, etc. Draw as many different layers as you need in order to find a pleasing combination of details.

Historic Effect & Balance

When contemplating your design, consider the overall effect. One feature that significantly stands out among historic gowns is that the entire costume is harmonious and balanced. A particular detail or shape from the overskirt might be echoed on the back of the gown, the sleeves, and on the bodice. Unlike today’s “mix and match” fashions, the Victorians often concentrated on complete looks—everything coordinated beautifully. Adjust the various design elements as necessary so that they go well together.

At the same time, keep a balance. Choose one part of the gown to have a spectacular feature; coordinate the rest of the costume, but keep it relatively subtle. Too many “feature” elements will clash. If you want an ornate bodice, for example, you could balance it out with some delicate trim on the lower half of the skirt, but nothing too bold. If the back of your Natural Form skirt is the centerpiece, then keep the front and sides uncomplicated, but do tie in some of the design to the front of the bodice. When considering trims, remember that certain periods were rife with ruffles and ribbons, while other periods had a simpler aesthetic.

Also, make sure that any unique design elements you come up with have a basis in Victorian costume. If you can’t find historic evidence of a particular feature that you like, then it might look too modern. However, if you’ve seen something similar, feel free to tweak it a little to make it your own. This is where your unique creativity will come into play.

Intermediate Design

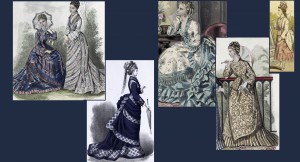

When I designed this mid-1870s day dress, I wanted to do something interesting—something not seen on your average beginner’s costume, but still using readily available patterns. I used a bodice, skirt, and overskirt pattern from Truly Victorian, but modified them to suit my design. For the bodice, I’d noticed examples of triple collars in several antique fashion plates, so I took that idea and ended up with a double collar.

I liked the look of layered overskirts, so I made a faux double apron.

For the sleeve cuffs, I echoed the design of the collar, giving the dress a more tailored feel, like several I’d seen in fashion plates.

The gown is not an exact copy of any one design, but is inspired by many gowns, and—importantly—has historic precedent.

Now, let’s walk through the design of an original 1876 ballgown.

One Response to Designing an Authentic Victorian Costume I