by Lisha Vidler

As with any subject, historic costuming is a field littered with misconceptions, fables, myths, and lies. Foremost among legends is the corset. This garment intrigues modern society, being a symbol of sexuality and the lengths to which women will go to achieve the ideals of fashion. Rumors are told of women who tight-laced down to thirteen inches, with waists the span of their husbands’ hands. There are whispers of women who surgically removed their lower ribs so as to attain a smaller waist, and of course, the ubiquitous stories of fainting, swooning, disfigurement, and even death.

A dramatic video on YouTube features a young Victorian woman dressing for a special occasion. Desperate to fit into her gown, she has her mother pull her corset strings tighter and tighter . . . until she falls down dead, the breath stolen from her lungs by the whalebone prison of her corset.

Are stories like this true? Did women suffer such cruelties for the sake of beauty? Are historic reenactors crazy because they want to dress accurately? First, let’s examine what a corset actually is and then we can address what it is not.

The Corset’s Purpose

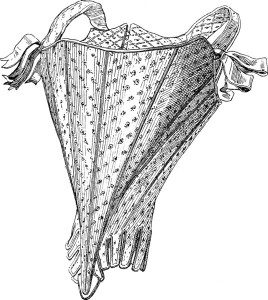

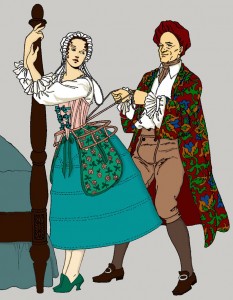

Looking at recent history, from about the 16th century onward, women wore corsets for three reasons: to support the breasts, to shape the figure, and to provide a sturdy foundation for the many layers of skirts and petticoats they wore. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the corset’s shape varied slightly, but generally the bust was compressed and lifted upward and the torso molded into either a cylinder or cone shape. These corsets could be wretched if their shape was exaggerated , but few took them to that extreme.

The shape began to change at the end of the 18th century. Instead of compressing the figure into a cone, corsets merely smoothed a woman’s natural shape so that it would look elegant beneath the popular dresses of thin muslin or gauze. It also lifted and separated the bust, which led to the term “divorce corset”. The addition of a solid wood busk down the center front encouraged good posture and made it difficult to slouch.

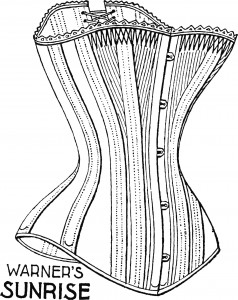

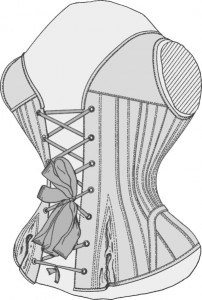

Starting in the mid-19th century, corsets began to fasten in the front with a metal two-piece busk. Spiral steel began to replace whalebone, and corsets became more flexible. Women began to desire an hourglass figure instead of the artificial shape that had previously reigned. This wasn’t accomplished wholly by corsets, however. A corset can only shift body fat—it can’t produce a shape that is entirely absent—so women often resorted to ruffles and padding to achieve the curved shape that was so popular.

A smooth, tailored bodice was critical for the fashionable woman of the late 1800s. To that end, corsets were crucial: instead of the lumps and bumps of a woman’s normal shape, a corset provided a smooth line from bust to hip. They typically reduced the waist no more than three or four inches, and this often made up for the bulk added by the waistbands of all the skirts and petticoats that were worn. Evidence suggests that a stylish woman wore between two and six petticoats, depending on whether the current silhouette was slender or full. She also wore a bustle, crinoline, or bum roll, in addition to her regular skirt, and in some decades, an overskirt. Each of these usually had its own waistband! As you can imagine, all those layers got heavy. A corset allowed the weight to be evenly distributed; it prevented the waistbands from cutting into a woman’s flesh and reduced the strain on her back.

In summary, corsets offer support to a woman’s bust, they smooth and shape her figure, and they provide a foundation for her garments. But what about all the horror stories? Now that we know what a corset does, let’s look at what it does not do.

Myth: Miniscule Waists

Part of this legend comes from Hollywood visions of a young woman heroically gripping the bedpost while being laced into her corset. It also comes, in part, from a misunderstanding about how corset sizing works.

Images of women struggling to lace their corsets have existed for centuries. In fact, a few women did tight-lace to dangerous extremes, more so in some periods than in others. But, like with most hazardous pursuits today, these women were in the minority. Most wore their corsets with moderation and good sense. How do we know?

There are thousands of corsets that have been preserved by museums and private collectors, as well as advertisements from catalogs and ladies’ magazines. By looking at these, we can see what sizes were common. But, you may ask, don’t antique corsets prove how tiny these women were? Not at all. It’s a misconception that a corset laces shut in the back, edge to edge. In fact, a corset is designed to have a reasonable gap between the back edges, anywhere from two to six inches. Add that amount to the waist measurement of a corset, plus the “squish factor”, or how much body fat is compressed when the corset is put on, and you begin to get a healthier perspective on the size. In other words, a corset that measures 18” is intended for a woman whose natural waist is anywhere from 20” to 28” in circumference. Not exactly Scarlet O’Hara!

What about photos of women with tiny waists? Some of these may be legitimate, but many of the photographs of women in corsets from the 19th century are well-known as having been touched up or edited to give the woman a smaller waist. And, of course, any drawings are suspect, for they could easily be sketched so as to give a smaller waist proportion than was strictly natural.

Myth: Surgically Removed Ribs

What about the stories of women who removed their lower ribs in order to have a smaller waist? Consider the fact that not a single documented case has been found where someone did this.

Add to that the simple truth that medicine in previous centuries was primitive at best. Not until the 1860s did scientists discover germs and realize the necessity to keep a sterile operating room! Even then, surgeons often went straight from the morgue to the operating theater without washing their hands or their instruments. This made surgery a risky prospect. Even a simple procedure, such as a tonsillectomy, could result in death; opening the chest cavity ran a much higher chance of infection. Then, too, anesthesia was risky, and pain medicines were dodgy. None of our ancestors would volunteer for a surgery they didn’t need—even for the sake of fashion.

~~*~~

Are corsets really painful or restrictive? What of tales of women who swoon, faint, or die because of their corsets? Do corsets deform the body? What about the assertion that only wealthy women wore corsets, because they needed a ladies’ maid to help them dress? These topics will be considered in the second half of this article: Exploring the Myths of Corsets II.

Pingback: Corset Myths | Yesterday's Thimble

Pingback: Things that don’t matter but I spend a lot of my time on them… Part One | lifeandthingsinbetween

Pingback: Corsetted Victorians and others – myths and reality | A Damsel in This Dress

Pingback: Sewing the Costumes for Blue Stockings – Empress of Buttons

Pingback: Dress All 1816 in 2016 – Now Then, Pittsburgh

Pingback: Improving Theatrical Costumes, Part 1 – Your Ward

Pingback: Improving Theatrical Costumes, Part 1 | Foundations Revealed